Anti-Colonial Science: A Course Journal. Vol. 2, 2024. https://ojs.library.dal.ca/acs/

Asitu'lisk: A Place of Flourishing

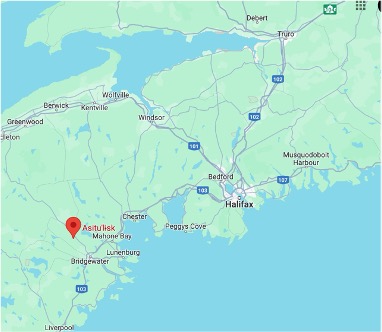

This summer, I spent one week living in the Wapane'kati forest in unceded Mi'kma'ki territory, now called “Asitu'lisk,” a Mi'kmaw word for “that which gives you balance.” This name was given to the land less than three years ago. Asitu'lisk is 200 acres of land under the full ownership and care of the Indigenous organization, Ulnooweg Education Centre. A unique example of non-metaphorical decolonization, the land was directly repatriated to Indigenous peoples from settler occupation. I spent my time there learning about the flourishing of Indigenous peoples through cultural revitalization initiatives and the flourishing of the Land through ecological revitalization efforts. In 2021, Asitu'lisk was returned to Indigenous peoples by the Dreschers, a settler family who owned the land since 1990 after purchasing it from another settler family. The Dreschers seemed to have a meaningful internal transformation on the path to the land relations present when I arrived. This reflection will share my experience of the Land following this transformation, and illustrate the community-based scientific practices that came out of centering Indigenous futurity.

The Mi'kmaq have been stewards of Mi'kma'ki for more than ten millennia. As I received a guided tour of the land, I was introduced to Grandmother Maple as a tree that has existed longer than settler-colonialism in Mi'kma'ki. Though the transition back to Indigenous ownership was a meaningful decolonial shift, it was nothing more than a reaffirmation of the land as unceded territory. Murphy writes, “decolonial futures can be found in the past,”1 and the stewardship of Asitu'lisk held a deep respect for the past. I see Asitu'lisk as a small-scale local example of decolonization and divestment from settler futurity. In "Decolonization is not a metaphor," Tuck and Yang argue that decolonization involves the direct repatriation of Indigenous land and life, not symbolic action that does not actively work to dismantle colonial power structures.2 As I spent time on the land, I could tell there was nothing metaphorical about Asitu'lisk's connection to present-day Indigenous lives. Asitu'lisk has been repatriated to Indigenous peoples, not through a land acknowledgement, or the vague notion that the landowners have "Indigenized" their minds. Asitu'lisk is under the direct care of Indigenous people and enlivened through sweat lodges, drumming, ecological projects, language classes and Mi'kmaw flourishing.

As a guest in Asitu'lisk, I travelled with a group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth who worked, reflected, gardened, shared, and healed with the land. This trip was through the HOWL Experience, an alternative educational project. It was founded by two high school teachers who found themselves disillusioned with the way their students, particularly their Indigenous students, were so often failed by an alienating public education system. It brings together youth for land-based experiential learning, community involvement, Indigenous knowledge sharing and intercultural learning, volunteerwork, and general joyfulness. It is difficult to ignore, of course, the tiny scale of this land repatriation compared to Mi'kma'ki or to dampen my apprehensions about the philanthropic status of the Indigenous organization running

Asitu'lisk (Ulnooweg) and its donors that sponsor it. And, of course, Indigenous people spending time in Asitu'lisk still live and are beholden to a settler-colonial state. However, I will not understate the meaningfulness of Asitu'lisk. To me, it felt like an example of the relinquishing of settler futurity and a restoration process that centers the desires of Indigenous peoples. It offered myself and a number of Indigenous youth from all across Turtle Island a feeling of what centering Indigenous futurity could look like in practice.

Before Mi'kmaq once again became the rightful stewards of this land, Grandmother Maple spent a generation or so with a settler couple, the Dreschers, a continuation of approximately eight generations of previous colonial occupation. The Drescher's relationship to the land during their ownership included a series of "settler moves to innocence."3 Two settler moves to innocence that the Dreschers made include Settler Adoption and Re-occupation/Urban homesteading. The couple applied sustainable forestry practices and enjoyed spending time with the land. In fact, in one Facebook post from several years ago, they thanked the Mi'kmaq and acknowledged the spiritual significance of the land. As one can't, in good faith, "thank" a person they've stolen from, this show of gratitude suggests a fantastical adoption narrative, as though a disappearing Mi'kmaq people gifted their land for them to continue on Mi'kmaw stewardship.

This relates to what Tuck and Yang call "going native," or adopting "the love of the land and therefore [think they] belong to the land."4 This imagined continuity leads to the second move to innocence, re-occupation and urban homesteading. Tuck and Yang call this "invoking Indigeneity as a "tradition" and claiming Indian-like spirituality while evading Indigenous sovereignty and the modern presence of actual urban Native peoples."5 Though the Dreschers claimed to be in good relation with the land in a way that attempted to mirror Indigenous stewardship principles, Grandmother Maple still felt the absence of the Mi'kmaq. However, much like some settler students I lived with during my stay, the previous landowners who relinquished their ownership seemed to undergo genuine transformation while living on the land. The past owner said in an interview: "[o]wnership is really a colonial remnant. And we're giving up that ownership quite happily."6 This quote presents Asitu'lisk as an example in which the “decolonization of the mind” surpasses acknowledgement, metaphor, gratitude and settler fantasy and culminates in decolonial action.

I believe the centering of Indigenous desires opens the door for stronger relational scientific practices, some of which I observed in my time at Asitu'lisk. Something she calls "exponentially generative," Tuck calls desire "both the part of us that hankers for the desired and at the same time the part that learns to desire" (Tuck 348). Asitu'lisk is home to many old-growth hemlock trees, which are threatened by invasive insects driven to Mi'kma'ki by climate change. A community of Mi'kmaw leaders, Elders, forest management workers, biologists and students work together in their desire to heal the hemlocks with a chemical treatment. As a guide led us through the hemlocks, his Two-Eyed Seeing approach resonated with Murphy's call for research that not only recognizes “the many worlds in which we exist” but stands strong in its responsibility to dismantle colonialism and work against notions that no such multiplicity exists.7 Wielding both lab-made chemicals, traditional knowledge of the Land and a profound concern for the holistic wellbeing of the trees as intimate relations at the same time, people spoke of the trees not as an “infested species” but as a beloved ecosystem they personally desired to heal. It seemed self-evident to the guide that both Elders and the local university would be called to heal the trees. Rather than imagining a discontinuity between science and Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge, I was struck that my guide's rhetoric held no exclusionary, rigid binary between a traditionally “scientific” (objective, disinterested, chemical) method of dealing with hemlocks and an “unscientific” (caring, invested, “natural”) method. Willing to inhibit multiple worlds, I watched an interdisciplinary team come together and do work that still centers Indigneous futurity and land stewardship. Therefore, I believe the lack of constraint on Indigenous desires in Asitu'lisk is deeply tied to the flourishing of Indigenous ecological knowledge.

Bibliography

Murphy, M. “Some keywords toward decolonial methods: Studying settler colonial histories and environmental violence from Tkaronto,” History and Theory, vol. 59, (2020), pp. 376-384.

Tuck, Eve. Suspending Damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), (2009), pp. 409–427.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society, no. 1, (2012), pp. 1–40.

Endnotes

Murphy, M. “Some keywords toward decolonial methods: studying settler colonial histories and environmental violence from Tkaronto,” History and Theory, vol. 59, (2020), pp. 383.↩︎

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society, no. 1, (2012), pp. 1–40.↩︎

↩︎Tuck and Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” 1.

Tuck and Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” 15. ↩︎

Tuck and Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” 28.↩︎

Grant, Taryn. “Historic N.S. property being transferred to Mi'kmaq in spirit of reconciliation,” CBC News (2020) https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/nova-scotia-windhorse-farm-sale-reconciliation-ulnooweg-mi-kmaq-1.↩︎

Murphy, M. “Some keywords toward decolonial methods,” 381.↩︎

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2024 Jessica Casey

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Works in Anti-Colonial Science: A course Journal are governed by the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International(CC BY-NC 4.0) license. Copyrights are held by the authors.