Anti-Colonial Science: A Course Journal. Vol. 3, 2025. https://ojs.library.dal.ca/acs/

Objectification and Obligation

Considering Methods of Land Relations

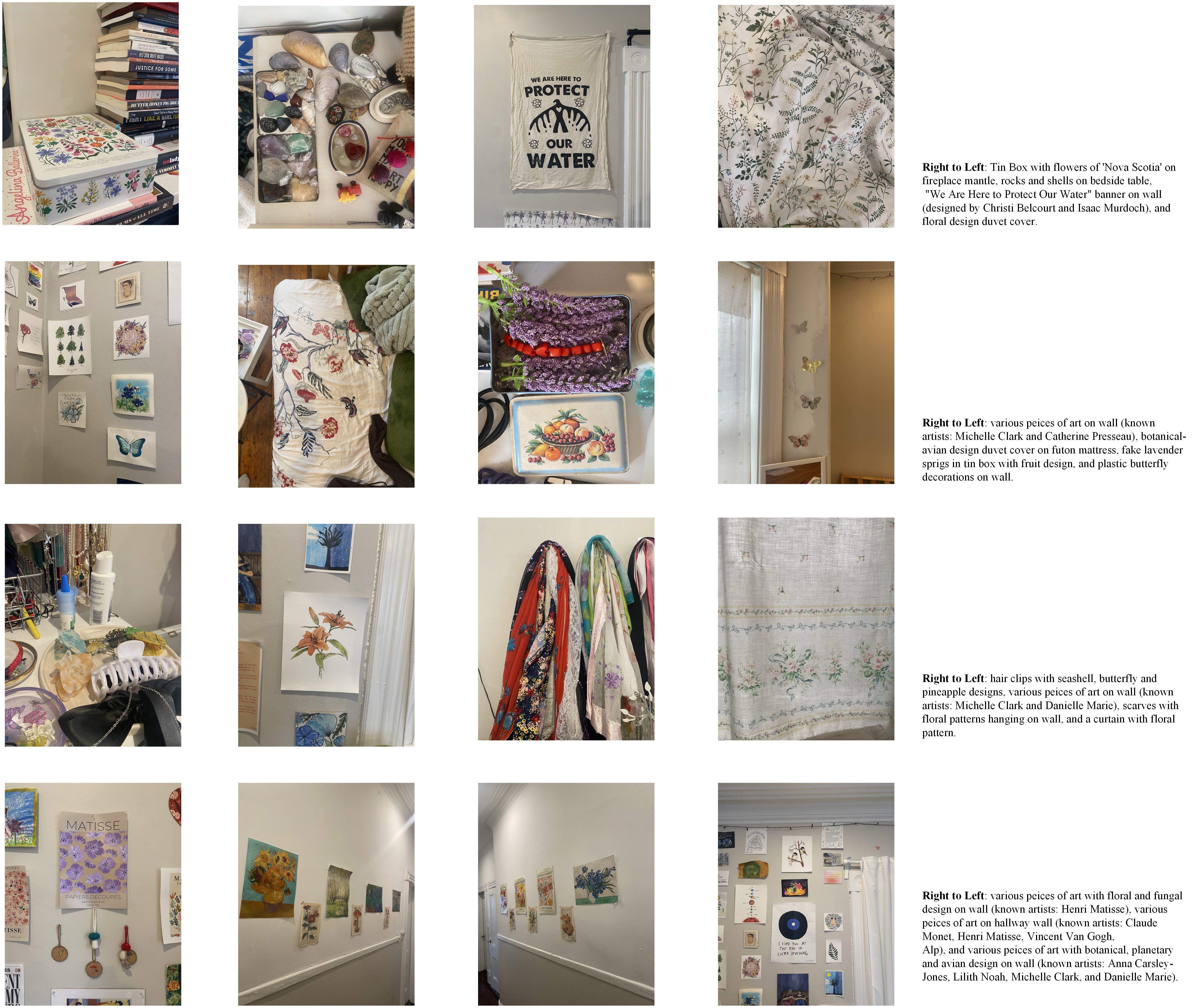

For my reflection, I chose to do a creative project to consider relationship(s) to Land, with focus on environmental science and the practice of resource extraction. I took coloured, eye-level photos with my iPhone of decorative aspects of my house, most taken in my room and some in the hallway. Each photo displays a being of the land or an artistic representation of the land (ex: a painting) that I have chosen to decorate my home with. I used my iPhone as it is my most accessible means of photography and I wished to display the ‘subjects’ of my photography as similarly to how they appear in person; I did not want to ‘distort’ what I was photographing with any filters, editing, focal length (zoom in/out) and so on. The one way I did alter photos was by cropping them, to either get rid of visuals that I felt were unnecessary or distracted from the main ‘subject’ of the photo, or to ensure that all photos could be sized with the same dimensions in my final display. I chose to use 16 photos, and have displayed in a 4x4 grid with image descriptions to the right of each row of 4.

These beings or the beings represented by artwork are presented because of my aesthetic appreciation and admiration for them. I believe that this visual appreciation does not necessitate an actual respect towards the land – it merely values land as an aesthetic object. Thus, I see these representations in my own home as indicative of a relationship to Land that is based in objectification, which reinforces Land as property/resource.1 This method of relation is exemplified by Homi J. Bhabha2 and challenged by both M Murphy3 and the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwepemc Nation,4 whose works my reflection benefits from.

From the wood that forms the structure of my house and makes my furniture and books, to the oil used to heat my house, to the electricity which powers lights, kitchen appliances and personal devices, to the material used to make such devices; I am surrounded by a web of products and practices dependent on resource extraction.5 As Homi J, Bhabha expressed in his Presidential Address, industrialization has permitted an increase in resource consumption that (literally) powers human life; “...energy... makes possible life itself [... and] as the total demand for energy increases, a larger and larger fraction will have to be provided by the fossil fuels, coal and oil...”.6 With the vast practice of resource extraction, often comes vast harm to Land and so an increased emphasis has been placed on scientific evaluation of this harm – prior to, during and/or after extraction. This is seen in the Environmental Assessments conducted by resource by governments7 and/or, such as in the case of the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwepemc Nation (SSN), by the local community(ies) itself, which evaluate the risk of environmental harm under a proposed project.

The SSN’s assessment report, created in response to the KGHM Ajax open-pit mine proposal in Pipsell, challenged the inadequacies of the federal and provincial (BC) environmental assessment processes and demonstrated the harmful interconnected impacts of the project, grounding the nation’s demand for more thorough assessment processes which respect their knowledge and sovereignty.8 The SSN rejected the objectifying approach of mainstream environmental assessments which privilege the scientific practice of individuals disconnected from the Land, often living hundreds of kilometers away. The community-led assessment asserts the necessary connection between the health of the nation and the health of the land, and so demands that what occurs within the Land should be decided by those who steward the Land - “our experts are those who live on land.”9 As the first Indigenous-grounded project assessment in North America of its kind,10 this report is evidence of a demand to enact a relationship of obligation towards Land and challenge behaviour based in objectification and exploitation.

M Murphy, a member of the Land and Refinery Project from the Indigenous Environmental Data Justice Lab in Tkaronto, also asserts a relationship of “obligation to capital-L ‘Land,’”11 working with the purpose of reducing the colonial violence enacted through environmental harm.12 Their project studies the Imperial Oil Refinery on the territory of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation (‘Sarnia, ON’), also referred to as Ontario's Chemical Valley as approximately 40% of Canada’s petrochemicals are produced in the area.13 The Imperial Oil Refinery depends on the resource extraction of oil and the environmental harm caused by the Refinery is evidence of the “structure of waste-making" upon which the petrochemical industry depends, “...that is, its ability to pollute freely.”14 Notably, the company owning the majority of Imperial Oil Limited is ExxonMobil,15 which is also responsible for Nova Scotia's most recent (1999-2018) natural gas production: Sable Offshore Energy Project.16 ExxonMobil also partially owns the Maritimes and Northeast pipeline,17 along with Enbridge Inc and Emera Inc — the former also being the owner of Nova Scotia Power.18 I believe these connections are crucial to understand; the company responsible for pollution within Aamjiwnaang Land also operates within Mi’kma’ki and has connections to the company that powers my house in Kjipuktuk. Murphy recognizes the far reach of resource extraction and its harm, and suggests that there are many methods of destabilizing the structures that exploit Land; “[d]ecolonial possibilities can be humble and need not be spectacular.”19

I believe that the work done by Murphy and their co-scholar by the Land and Refinery Project, and the SSN’s assessment report, are evidence of environmental science practices within Land which challenge objectification and emphasize obligation. In walking around my house and taking these photos, I felt what I identify as hypocrisy – I have surrounded myself by beings or representations of the Land and yet I am also surrounded by an exploitative structure dependent on resource extraction. I do not have a simple solution to this tension and perhaps this is what Murphy would note as an incommensurability,20 yet I claim responsibility in nurturing a relationship of obligation to Land as a living counterpart and reducing-rejecting my involvement in practices that assert colonial objectification of Land as resource and/or property.

Bibliography

Alp, Set of 5 flower dictionary print, 9x6 in, Kjipuktuk.

Alp, Set of 7 art prints on old dictionary print, 9x6 in, Kjipuktuk.

“Basics of Environmental Assessment under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012.” Impact Assessment Agency of Canada. Last modified March 26, 2025. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.canada.ca/en/impact-assessment-agency/services/policy-guidance/basics-environmental-assessment.html.

Bhabha, Homi J. “Presidential Address.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy. Delivered August 8, 1955. Record of the Conference. Vol. 16. United Nations: New York, 1956: 31–35. Accessed on HSTC3403 Brightspace.

“Canada.” Maritimes & Northeast Pipeline. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.mnpp.com/canada.

Carsley-Jones, Anna, unnamed pieces, paint and pencil, Kjipuktuk.

Christi Belcourt and Isaac Murdoch, We Are Here to Protect Our Water, ink on fabric, 35x22 in, Kjipuktuk.

Clark, Michelle, various unnamed pieces, print, 5x7in, Kjipuktuk.

Danielle Marie, Lovely Lilies, print, 10x8 in, Kjipuktuk.

Danielle Marie, Chickadee Dee Dee, print, 10x8 in, Kjipuktuk.

Danielle Marie, Solar System, print, 11x8.5 in, Kjipuktuk.

“ExxonMobil in Canada.” ExxonMobil Corporation. May 30, 2024. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/locations/canada#Exploremore.

Matisse, Henri, Papiers Decoupes series, 1951, print, 15x10 in, Kjipuktuk.

Monet, Claude, The Artist’s Garden at Giverny, 1900, print, 10x10 in, Kjipuktuk.

Monet, Claude, Woman Seasted under the Willows, 1880, print, 13x10 in, Kjipuktuk.

Murphy, M. “Some Keywords toward Decolonial Methods: Studying Settler

Colonial

Histories and Environmental Violence from Tkaronto.” History and

Theory 59 no. 3. (2020): 376–384. Accessed on HSTC3403

Brightspace.

Noah, Lillith, love song, print, 16x11.7 in, Kjipuktuk.

Presseau, Catherine, Affiche Arbres du Québec, print, 10x8 in, Kjipuktuk.

“Provincial and Territorial Energy Profiles – Nova Scotia.” Canadian Energy Regulator. Last modified September 10, 2024. Accessed March 15, 2025. https://www.cer-rec.gc.ca/en/data-analysis/energy-markets/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles-nova-scotia.html.

“Sable Offshore Energy Project.” ExxonMobil. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/-/media/global/files/locations/canada-operations/sable-overview.pdf.

Stk’emlúpsemc Te Secwepemc Nation. “SSN Lessons from the Land: Written Submission.” Prepared for the CEAA Expert Panel by Stk’emlúpsemc Te Secwepemc Nation. (2016): 1-22. Accessed on HSTC3403 Brightspace.

Van Gogh, Vincent, Irises (in soil), 1889, print, 12.5x10 in, Kjipuktuk.

Van Gogh, Vincent, Irises (in vase), 1889, print, 12.5x10 in, Kjipuktuk.

Van Gogh, Vincent, Sunflowers F 455, 1889, print, 13x10, Kjipuktuk.

“Who We Are.” Nova Scotia Power. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.nspower.ca/about-us/who-we-are.

- ↩︎

M. Murphy, “Some Keywords toward Decolonial Methods: Studying Settler Colonial

Histories and Environmental Violence from Tkaronto,” History and Theory 59, no. 3 (2020): 379, accessed on HSTC3403 Brightspace. - ↩︎

Homi J. Bhabha, “Presidential Address,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy, delivered August 8, 1955, Record of the Conference ,vol.16, (1956): 31–35, accessed on HSTC3403 Brightspace.

- ↩︎

Murphy, “Some Keywords toward Decolonial Methods,” 376–384.

- ↩︎

Stk’emlúpsemc Te Secwepemc Nation, “SSN Lessons from the Land: Written Submission,” prepared for the CEAA Expert Panel by Stk’emlúpsemc Te Secwepemc Nation (2016): 1-22, accessed on HSTC3403 Brightspace.

- ↩︎

“Provincial and Territorial Energy Profiles – Nova Scotia,” Canadian Energy Regulator, last modified September 10, 2024, accessed April 7, 2025, https://www.cer-rec.gc.ca/en/data-analysis/energy-markets/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles-nova-scotia.html.

- ↩︎

H. J. Bhabha, “Presidential Address,” 31-33.

- ↩︎

“Basics of Environmental Assessment under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012,” Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, last modified March 26, 2025, accessed April 8, 2025, https://www.canada.ca/en/impact-assessment-agency/services/policy-guidance/basics-environmental-assessment.html.

- ↩︎

Stk’emlúpsemc Te Secwepemc Nation, “SSN Lessons from the Land: Written Submission,” 4.

- ↩︎

Stk’emlúpsemc Te Secwepemc Nation, “SSN Lessons from the Land: Written Submission,” 15.

- ↩︎

Stk’emlúpsemc Te Secwepemc Nation, “SSN Lessons from the Land: Written Submission,” 3.

- ↩︎

Murphy, “Some Keywords toward Decolonial Methods,” 379.

- ↩︎

Murphy, “Some Keywords toward Decolonial Methods,” 377.

- ↩︎

Murphy, “Some Keywords toward Decolonial Methods,” 377.

- ↩︎

Murphy, “Some Keywords toward Decolonial Methods,” 378.

- ↩︎

“ExxonMobil in Canada,” ExxonMobil Corporation, May 30, 2024, accessed April 8, 2025. https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/locations/canada#Exploremore.

- ↩︎

“Provincial and Territorial Energy Profiles – Nova Scotia,” Canadian Energy Regulator; “Sable Offshore Energy Project,” ExxonMobil.

- ↩︎

“Canada,” Maritimes & Northeast Pipeline, accessed April 8, 2025, https://www.mnpp.com/canada.

- ↩︎

“Who We Are,” Nova Scotia Power, accessed April 8, 2025, https://www.nspower.ca/about-us/who-we-are.

- ↩︎

Murphy, “Some Keywords toward Decolonial Methods,” 382.

- ↩︎

Murphy, “Some Keywords toward Decolonial Methods,” 381.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Anna Carsley-Jones

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Works in Anti-Colonial Science: A course Journal are governed by the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International(CC BY-NC 4.0) license. Copyrights are held by the authors.